Celebrating a Century of Excellence

“

“

"It’s certainly been a love affair for me.”

That is how John Mullen describes his 38 years at Cheverus High School in Portland, nine of them spent teaching, two as assistant principal, and 27 as acting principal and principal. He retired in 2016 only to find himself drawn back to the classroom again.

“I’ve been blessed to work under great mentors, to work with spectacular colleagues through the years,” he says. “It’s been a tremendous experience for me to grow professionally in this Jesuit, Catholic community.”

He says he never intended to make teaching his career, but that first class changed everything.

“When I finished that first semester of teaching the one class, I really had fallen in love with teaching,” he says.

Teachers and staff members like Haskell and Mullen have helped shape the lives of thousands of students during their time at Cheverus, carrying on a tradition that began a century ago.

The school was established in 1917 by Bishop Louis Walsh as a diocesan boys’ school. It was originally called Catholic Institute High School and was located in the Sisters of Mercy former motherhouse on Free Street, not far from where the Cumberland County Civic Center sits today. The first class of 46 boys were taught by diocesan priests and Sisters of Mercy.

In 1925, the school’s name was changed to Cheverus in honor of Bishop Jean Lefebvre de Cheverus, the first Bishop of Boston, known for his missionary work in Maine. In 1942, the Society of Jesus (the Jesuits) took over operation of the school, and four years later, the Free Street building was sold to Sears, Roebuck & Co., and the school moved next to the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception. It would not remain there long. In 1950, a supporter of Catholic education donated $500,000 for a new school, which was built on Ocean Avenue. The diocese deeded the land to the Jesuits, who have owned and operated Cheverus ever since.

“One of the things I love about the Jesuits is that they have such a strong faith that they’re never afraid that if they lift this intellectual rock, they won’t find God,” Haskell says. “They’ll go anywhere, and look at anything, and encourage their students to do so.”

That mission is to prepare young men and women to be people for others by fostering intellectual, spiritual, physical, and personal excellence. While Jesuits no longer fill the classrooms and hallways as they once did, the commitment to that mission remains as strong as ever. In fact, Mullen and Haskell say, if anything, they’re even more intentional about making it known now than they were decades ago.

“When the numbers dwindled, we decided that we really needed to take a hold of the mission, and get our hands into it, and understand it, and embrace it,” says Mullen. “We do it by engaging with students, incorporating the mission in our curriculum, into all our courses by providing programs for them.”

Mary Lee King, a theology teacher at Cheverus for the past 20 years, has embraced that wholeheartedly.

“One of the things that we teach a lot about is Catholic social teaching,” she says. “I always say that love in the public sphere is justice. We can love interpersonally in our homes and in our relationships, but in a communal, public sphere, the way that you love is you try to ensure and you try to discover what is fair and just.”

It’s a message she tries to communicate within the classroom, as well as far beyond the school’s walls. She established a Haiti Solidarity Club to raise awareness about poverty in developing countries. She helped launched an international immersion trip program that took students to the Dominican Republic. And this year, she and another teacher accompanied students on a trip to the Arizona-Mexico border, so they could gain firsthand knowledge about immigration issues

“Had I planned a whole year on immigration and done a course, you wouldn’t have learned as much as you did in those five days, being there and meeting people,” says King.

|

|

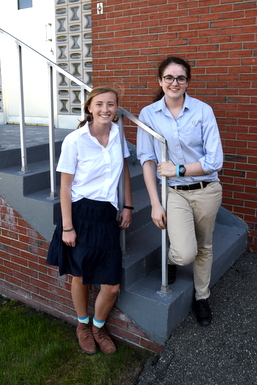

“I had my opinion, but I didn’t really know anything to back it up. So, going on this trip gave me a chance to lift my veil of ignorance and learn more about it,” says Karen Nielsen, a senior.

“I realized that there was so much that I didn’t know before I went. I knew the issues from a policy standpoint, and I felt that people should be given due justice, but I didn’t really know the human aspect,” says Eva Griffiths, a senior.

Embracing the principles of Pope Francis’ encyclical Laudato Sí, King and two colleagues also created the Ignatian Carbon Challenge.

“Every month, people who sign up for this get a series of challenges that help them to become better stewards of the environment,” she explains.

The program, now in its second year, has proven so popular that students around the country are participating and, through a hashtag, are sharing their experiences.

“Just like with immigration, Pope Francis’ whole thing was to make climate change a human issue,” says King. “It’s about recognizing our obligation and our connection to humans around the world.”

One of the ways the school helps students recognize that human connection is through service.

“Our lives aren’t about us. That’s what we learn here a lot. It’s emphasized in every class, not just theology,” says Racheal Haskell, a senior and Dan’s daughter.

Cheverus students must complete a four-year service plan, culminating with an Arrupe Service Project. Named for Father Pedro Arrupe, S.J., a former superior general of the Society of Jesus, students spend the final month of their senior year focusing entirely on service work, volunteering at places such as nursing homes, daycare centers, and elementary schools.

“It really is one of the cornerstones of Jesuit education to expose them to the importance of serving, to try to ingrain in them the importance of service,” says Mullen. “It’s very much at the fiber of Cheverus.”

While Cheverus welcomes students from all religious traditions, the Catholic faith remains at the heart of the school’s call to serve its students and others. The school year starts with the Mass of Holy Spirit, which this year was celebrated by Bishop Robert Deeley. School days start with prayer and include time for reflection.

“We pause every day at 10:10 for what we call a daily examen, an examination of conscience, which is an exercise introduced by the Jesuits many years ago where we stop and pause and consider where God is in our life at that time and what we might do to perhaps feel God’s presence more prominently,” Mullen explains.

Each year, students also go on a retreat, from an overnight stay at the school for incoming freshmen to the three-day, offsite Kairos retreat for seniors.

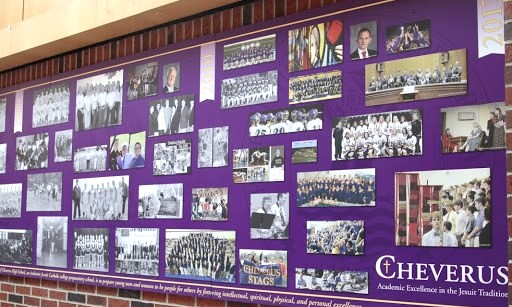

As shown on a history wall that Mullen helped to create for the school’s 100th anniversary, Cheverus has seen many changes through the years. One of the most significant was the decision to go coed. In 2000, the school welcomed its first female students, 25 in all. It was a difficult transition for some but viewed as necessary.

“It was mostly a philosophical belief that it was just time in our world, our very coed world, our diverse world, that we include girls at Cheverus High School,” says Mullen. “And, undeniably, there was a business interest as well, in that it would deepen the pool of students.”

“I think we lost a few things, but in balance, I think we’re far, far richer with young women here,” says Haskell. “I am very pleased that my daughters get to graduate from Cheverus High School.”

Two of Haskell’s children have already joined him as Cheverus alumni. Two others attend now, and he hopes three in elementary school will continue what has become a family tradition.

“There is no other place you can go where your child will be valued for who they are, asked to develop every part of who they are, the physical, social, spiritual, emotional, not for their own good but understanding that their own good is ultimately tied to the loving God in the community in which God is revealed,” says Haskell. “Your education isn’t about you. It’s about love.”

“I learned a lot from Cheverus, particularly, that my education is not about me; it’s about something more,” agrees Racheal. “It’s about justice and using the education and the privilege I’ve been given to pass it on to someone else.”

“There is always going to be a place for Cheverus High School because of the mission it provides, the special atmosphere it provides,” says Mullen. “I see us thriving in the future.”